- Home

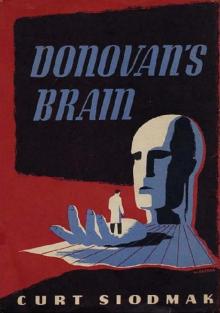

- Curt Siodmak

Donovan’s Brain

Donovan’s Brain Read online

Table of Contents

DONOVAN’S BRAIN SEPTEMBER 13

SEPTEMBER 14

SEPTEMBER 15

SEPTEMBER 16

SEPTEMBER 16

SEPTEMBER 17

SEPTEMBER 18

SEPTEMBER 19

SEPTEMBER 25

SEPTEMBER 30

OCTOBER 2

OCTOBER 3

OCTOBER 6

OCTOBER 7

OCTOBER 10

OCTOBER 12

OCTOBER 14

OCTOBER 16

OCTOBER 17

OCTOBER 18

OCTOBER 19

OCTOBER 20

OCTOBER 21

OCTOBER 25

OCTOBER 27

OCTOBER 30

NOVEMBER 3

NOVEMBER 5

NOVEMBER 6

NOVEMBER 10

NOVEMBER 11

NOVEMBER 12

NOVEMBER 21

NOVEMBER 22

NOVEMBER 28

NOVEMBER 29

DECEMBER 2

DECEMBER 3

DECEMBER 4

DECEMBER 5

DECEMBER 6

DECEMBER 8

DECEMBER 9

DECEMBER 10

DECEMBER 11

DECEMBER 12

DECEMBER 13

DECEMBER 18

MAY 15

MAY 20

NOVEMBER 22

DECEMBER 5

DECEMBER 13

DECEMBER 15

DECEMBER 17

MAY 21

JUNE 1

JUNE 2

JUNE 5

JUNE 10

DONOVAN’S BRAIN

BY

CURT SIODMAK

DEDICATION

TO HENRIETTA

SEPTEMBER 13

Today a Mexican organ-grinder passed through Washington Junction. He carried a small Capuchin monkey which looked like a wizened old man. The animal was sick, dying of tuberculosis. Its moth-eaten fur was tawny olive, greasy, and full of hairless patches.

I offered three dollars for the monkey, and the Mexican was eager to sell. Tuttle, the drugstore-owner, wanted to keep me from buying it, but he was afraid to interfere lest I stop patronizing his place and make my purchases in Konapah or Phoenix.

I wrapped the flea-ridden Capuchin in my coat and carried it home. It shivered in spite of the burning heat, but when I held it closer, it bit me.

The animal trembled with fear as we entered my laboratory. I chained it to the leg of the work table, then washed my wound thoroughly with disinfectant. After that, I fed the creature some raw eggs and talked to it. It calmed down—till I tried to pet it, then it bit me again.

Franklin, my man, brought me a cardboard box which he had half-filled with hemp. The hemp would smother the fleas, he explained. My monkey nimbly hopped into the box and hid there. When I paid it no further attention, it soon fell asleep. I studied its almost hairless face, its head covered with short fur that resembled the cowl of a Capuchin monk. The animal was breathing with difficulty and I was afraid it might not live through the night.

SEPTEMBER 14

The monkey was still alive this morning and screamed hysterically when I tried to grab it. But after I fed it bananas and raw egg again, it let me pet its head a moment. I had to make it trust me completely. Fear causes an excess secretion of adrenalin, resulting in an abnormal condition of the blood stream; this would throw off my observations.

This afternoon, the Capuchin put its long arms around my chest and pressed its face against my shoulder, in perfect confidence. I stroked it slowly, and it uttered small whimpers of content. I tried its pulse, which was away above normal.

When it began to sleep in my arms, I stabbed it between the occipital bone and the first cervical vertebra. It died instantly.

SEPTEMBER 15

At three o’clock this afternoon Dr. Schratt came from Konapah to visit me. Though I often do not see him for weeks at a time, we communicate freely by phone and letter. He is very interested in my work but, as he watches my experiments, he cannot hide his misgivings. He does not conceal his satisfaction when he sees me failing in an experiment. His soul is torn between a scientific compulsion (which is also mine), and a pusillanimous reaction against what he calls: “invading God’s own hemisphere.”

Schratt has lived in Konapah for more than thirty years. The heat has dried up his energies. He has become as superstitious as the Indians of his district. If his medical ethics permitted, he would prescribe snake charms and powdered toads for his patients.

He is official physician for the emergency landing field at Konapah, and the small sum paid him by the airline keeps him from starving. There is not very much business around here to feed a country doctor. The few white people go to the hospital in Phoenix when they are ill; the Indians only call a white doctor when all the mystic charms have failed and the patient is dying.

Schratt once had the makings of a Pasteur or a Robert Koch. Half drowned in cheap tequila now, he has lost the ability to concentrate. But still sometimes a flash of genius illuminates the twilight of his consciousness. Afraid of that lightning-flash of vision, he deliberately withdraws into the haze of his slowly simmering life.

He watched me this afternoon with fatherly hatred. If he could forbid me to do what I am doing, he would. But forgotten wishes and dreams sometimes echo in the ruins of his wretched life. His antagonism to me and my work is pure manifestation of his regret that he has betrayed his own genius.

Sitting in a deep chair near the fireplace, he smoked his pipe nervously. How he can stand the desert heat in that thick old coat he brought from Europe forty years ago I shall never know. Maybe it is the only one he has.

I am quite sure that each time he leaves me he takes an oath never to see me again. But every few days my telephone rings and his hoarse, tired voice asks for me—or his aged Ford stops, boiling, in front of my house.

I had dissected the monkey’s carcass. The lungs were infected with tuberculosis, which had also attacked the kidneys. But the brain was in good shape. To preserve it, I placed it in an artificial respiratory.

I fixed rubber arteries to the vertebral and internal carotid arteries of the brain, and the blood substance, forced by a small pump, streamed through the circle of Willis to supply the brain. It flowed out through the corresponding veins on both sides and passed through glass tubes which I had irradiated with ultraviolet.

The strength and frequency of the infinitesimal electric charges the brain was producing were easy to measure. The electroencephalograms marked their slow, trembling curves on the paper strip which continuously flowed from the wave-recording machine.

I was very eager to hear Schratt’s comment on my success, but he only stared, irritated, at the wavering line which scrawled an irregular frieze pattern on the paper strip.

He lifted his thick brown fingers and touched once the glass in which the brain was floating. Immediately, disturbed, the brain-waves altered, rose and fell with ever increasing rapidity. The detached organ was reacting to an external stimulus!

“It feels—it thinks!” Schratt said. When he turned around I saw the spark in his eyes I had eagerly expected.

But Schratt sat down heavily. As he thought of what he had seen, he grew pale under the coarse, brownish skin that loosely covered his drink-sodden face.

“You’re the godfather of this phenomenon,” I said to cheer him up, in spite of knowing he could not be flattered.

“I don’t want any part of anything you are doing, Patrick,” he answered. “You, with your mechanistic physiology, reduce life to physical chemistry! This brain may still be able to feel pain; it may su

ffer, though bodyless, eyeless, and deprived of any organ to express its feeling. It may be writhing in agony!”

“We know that the brain itself is insensitive,” I answered quietly. To please him I added: “At least we believe we know that!”

“You have put it in a nutshell,” Schratt answered, I perceived that he was trembling; the success of my experiment had unnerved him. “You believe and acknowledge only what you are able to observe and measure. You recklessly push through to your discoveries with no thought of the consequences.”

I had heard him express this view before.

“I only try to cultivate living tissues outside the body,” I patiently answered. “You must agree, in spite of your abhorrence of everything concerned in the progress of science, that my experiment is a big step forward. You told me the fragility of nervous substance is too great to be studied in the living state. But I have done it!”

I touched the glass which contained the Capuchin’s brain, and the encephalograph at once registered the reaction of the irritated tissues.

I watched Schratt closely. I wanted to have from him again that admixture of genius which fertilized my researches. But Schratt’s expression was blank and remote.

“You’re synthetic and concise,” he finally said unhappily. “There’s no human emotion left in you. Your passion for observation and your mathematical precision have killed it, Patrick. Your intelligence is crippled by a profound inability to understand life. I am convinced that life is a synthesis of love and hatred, ambition and aimlessness, vanity and kindness. When you can manufacture kindness in a test tube, I’ll be back.”

He walked slowly and forlornly to the door, as always when he had made up his mind to break with me. But in the doorway he turned and added in a trembling voice: “Do me a favor, Patrick! Shut off the pump. Let that poor thing in there die!”

SEPTEMBER 16

After midnight the deflections of the encephalograph ceased, and the monkey’s brain died.

The telephone in the living-room rang at three in the morning, while I was still working in the laboratory. I heard the bell shrill faintly again and again. Janice had gone to bed hours ago, after bringing me some supper on a tray.

Obviously she had taken a sleeping draught, or the bell’s persistent ringing would have wakened her. Franklin, who slept in the cottage in the back, would never get up.

When I finally took down the receiver, I heard Ranger White’s excited voice. A plane had crashed near his station.

“I can’t reach Konapah!” White shouted as if he had to talk to me across the distance without the help of a telephone. “Old Doc Schratt is drunk again.”

He began to swear, out of control of himself—a man alone in a blockhouse on top of a mountain, eight hard miles from the nearest dwelling, with a crashed plane close to him.

He had tried Schratt for ten minutes before he switched the call to me. He had only two lines to choose from—Schratt’s and mine. The telephone operator leaves these connections open all night in case of emergencies.

I calmed White down and promised speedy help.

Finally I got Schratt on the phone. He could hardly talk or even understand what I was telling him. I repeated the information again and again.

“I can’t get up there!” he whined when my words had penetrated his tequila-fogged brain. “I can’t. I’m an old man. I can’t sit on a horse for hours. I’ve got a bad heart!”

He was deadly afraid of losing his job, but the alcohol had paralyzed him.

“All right, I’ll take over for you,” I said. “Meet me at my house tonight.”

“At your house tonight, Patrick,” he repeated plaintively. “Thanks, Patrick. Thanks….”

To wake Franklin from his sleep was a job. I ordered him to call the neighbors and to get me some help. Then I went back to the laboratory and packed my bag with all the instruments and medication I thought I would need. When I looked up, Janice stood in the door.

She had put on her morning gown and with thin fingers was trying to fasten the belt at her waist. Her eyes were tired and dull. She had drugged herself. I saw that at once.

She cannot bear the climate, the heat of the parched desert, the sudden sandstorms, the stale water that is pumped through miles of hot pipelines. She was withering away slowly, desiccating. I had told her often enough to leave Washington Junction. She should live in New England, where she was born. But she will not leave me.

“Emergency?” she asked, pulling herself together, battling the drug.

I told her about the plane and White’s call.

“Let me go with you,” she asked, but her tongue was thick “I can help….”

She was suddenly awake, restless. I knew she only wanted to be with me, close to me, and the crash was a pretext.

“No,” I said, “you’re not fit for the trip. Go to bed.”

I realized I had not talked to her for weeks. Her shadow was always behind me—my food in my room at the right moment, the house cleaned noiselessly, and she never bothered me with questions. She was waiting for me to call her, but I had forgotten her shadowy existence.

The men arrived with the horses and mules. We went up the mountain trail.

SEPTEMBER 16

Our horses had climbed for three hours when we came to White’s ranger station. It is a blockhouse of heavy timbers and a tower from which the observer has the wide view over the mountains. White’s job is to keep lookout for fires and see that the batteries for the revolving lights are charged properly. The beacons are landmarks for planes flying to the north and west.

White is a man of about fifty. He lives with only his dog in this lonely place. To him even the few inhabitants of Washington Junction are an unbearable crowd. Now, for the first time, I found him wanting to see someone, anyone. His weather-browned face looked livid.

“Glad you came,” he said, helping me from my horse.

As he led me to the plane, he added: “It’s an awful mess!”

There was not much left of the ship. The impact of the crash had disintegrated the wings, cabin, and fuselage. Pieces of the plane were scattered over a wide area. It looked as if the pilot had misjudged the height of the mountain.

“It caught fire, but I got it out,” White said, and pointed at a still smoldering patch where the blackened gas tank had burst inside out.

“I hope they’re still alive.” White had done an efficient job in spite of his shock.

He had carried the two survivors into the shade under a tree. One was a young man, the other an older man whose face seemed familiar. Both were still breathing. The young one had his eyes open, but he did not see me. He was semiconscious and his teeth were embedded in his lower lip. A trickle of blood ran down his chin.

I gave him a shot of morphine and turned to the other man. This one had compound fracture of both legs. White had twisted a tourniquet above each of the man’s knees to keep him from bleeding to death.

Tuttle and Phillips approached, but stopped a few yards from the injured men. I did not see Matthews, the third man. He had told me on the way up he could not stand the sight of blood.

Tuttle said: “There’re two more guys over there, but they are dead!”

I turned in the indicated direction and saw a propeller buried in the ground, with a part of the motor still attached.

“Their heads are off.” Phillip’s voice was so low I could not understand him at first.

White had found four bodies. The plane, though powerful, was too small to have carried more.

I ordered White and Phillips to take the older man to the blockhouse. I examined the young man where he lay. His chest was crushed and both arms broken. I told Tuttle to cut four straight branches from the tree.

The man was conscious but could not talk. The morphine had lessened his pain; he was perspiring profusely. His pulse was close to a hundred and ten.

“Take it easy, try to doze off,” I told him. “Don’t fight. You’ll be all right.”

&

nbsp; He seemed to understand and tried to answer. But the drug was already taking effect, closing his eyes.

I moved his arms carefully across his chest, and padding with bandages the four branches Tuttle had brought me, I laid them against both sides of the humerus and tied them securely at wrist and elbow. I gave the man a second injection to keep him asleep until we got him to the hospital and ordered Tuttle to take him down to Washington Junction, where he would meet the ambulance.

Tuttle called Phillips and they tied the unconscious man on a stretcher. I went back to the house without waiting for them to leave.

White had placed the old man on a table. He was beginning to stir and groan as I loosened the tourniquets from around his legs, which were swelling rapidly.

“They will have to be amputated,” I said to White, “or he will die in a few hours.”

White turned his livid face toward me and nodded. He grinned in an effort to control himself, but I was afraid he would never stick it through.

Now I regretted not having brought Janice. Matthews, the grocer, the only other helper I had still with me, was outside being sick. He had never seen broken bones and mangled bodies before. I talked to him, but he was no help.

I gave White a bromide to calm him down. He became very efficient, carried out all my orders with speed and precision. But he could not stop talking. I let him talk, for it seemed to relieve him. He kept explaining just what had happened.

He had heard the ship cruising overhead soon after midnight. It seemed to have lost its bearings. The beacons were all in working order, but the clouds were unusually thick. White was at a loss to know what plane it was. The commercial from Los Angeles had already passed, and no other information had come from Konapah.

White talked in a staccato voice while he gathered fresh bed linen and white shirts from a drawer. He fired the kitchen stove and put water on to heat, efficient but mechanical. I scrubbed the kitchen table with green soap, which he fortunately had in the house.

Donovan’s Brain

Donovan’s Brain