- Home

- Curt Siodmak

Donovan’s Brain Page 13

Donovan’s Brain Read online

Page 13

“You, as a lawyer, are obligated to secrecy in the affairs of your clients, and I am one of them,” I said.

“I know my duty very well, Dr. Cory,” Fuller answered, with a sly undertone.

“Then why have you forgotten it?” I asked.

“Why did you spend money on that murderer?” Howard Donovan accused in a theatrical voice. He stood behind me and I had to turn in my chair to face him.

“What murderer?”

“This Cyril Hinds, or whoever he is!”

Howard’s face was as grave as a judge’s.

“You don’t know why?” I was surprised.

“No—but you are using my father’s money!” he pointed a fat accusing finger at me. I had to laugh.

Howard was speechless. He looked to Fuller for help.

“Please, let me do the talking for a minute,” the lawyer said with elaborate caution. “You are thirty-eight years old, Dr. Cory. You studied medicine at Harvard. When you were twenty-nine you married a girl of small independent means. For a few years you practiced in Los Angeles, but you never earned great sums of money. Then you retired to Washington Junction to carry out some experiments, living on the money you had saved, and afterwards on your wife’s.”

“Right,” I said. “That is my life story.”

Fuller went on patiently. “Suddenly you are in possession of seemingly limitless funds….You gave up your experiments and moved back to Los Angeles, interesting yourself in people you had never seen before, like Hinds and Sternli….” He was dryly adding up the facts as if they were crimes committed.

I interrupted. “How does this concern you, or Mr. Howard Donovan?”

Howard could not keep silent. “Remember our conversation in Phoenix? You denied that my father had talked to you and he told you where he hid his money!”

I stared at him coldly and the silent duel broke his control. His face grew livid and he shouted: “It’s my money and you stole it!”

“This is a peculiar accusation, and you will have to prove it,” I answered, amused, but in the back of my mind I was afraid.

“Where did you get the money you are throwing around?” Howard cried.

I got up and walked over to the writing-desk, limping. I felt the dull pressure in my kidneys as I sat down heavily.

“Perhaps Mr. Fuller can conjure up some legal reason why I should answer!”

Fuller’s voice was smooth and unaggressive. “We can settle this amicably, Dr. Cory. Mr. Donovan is prepared to give you ten per cent of the sum his father left in your trust at the moment of his death. Furthermore the money you have spent or disposed of up to now will not be questioned.”

“Any amount?” I asked, looking straight into Fuller’s eyes.

He knew I meant the fifty thousand dollars I had put aside for him, but he did not flicker an eyelash.

“Of course,” he replied in a friendly tone.

“All right. Will you put that in writing?” I went on.

I saw Howard’s eager expression, Fuller’s sphinx like smile. Chloe’s face shone white in the half-dark like a grinning death’s head.

“Just sign this first.” Fuller took a paper from his pocket and put it down in front of me. It was a statement that I had used Donovan’s money. I did not bother to read through the paragraphs.

My left hand took the pen and I wrote: “Money received for stamp collection. W. H. Donovan.” The pen encircled the name with an oval.

Howard stepped close to pick up the paper. He glanced at the sentence and signature, with eyes that started from their sockets. Struck dumb, he moved his colorless lips. His fingers, limp, dropped the paper on the floor.

Fuller had watched him closely. “What is it?” he asked, alarmed, and bent down to pick up the paper. But Chloe, having noiselessly left her chair, put her foot on it, stared, and bent down.

Suddenly she clutched her throat and broke into endless hysterical laughter; her face twisted and spots of color sprang out on her white cheeks. She laughed, unable to breathe, until her face, lips, and ears turned cyanotic. The pupils of her eyes dilated widely, failing to react to light stimuli.

Stepping over to her quickly, I held her arm with my right hand and struck a sharp blow close to her left clavicle. As I saw her eyes grow normal again, I slapped her face twice, hard, holding her up.

The laughter stopped; she could breathe now, but collapsed in my arms as I had expected. I carried her over to the couch and put her down, her face to the wall.

Howard watched me, petrified.

Chloe began to cry, uncontrollably, her body shaking with convulsive sobs.

“Get me a sedative, quickly!” I looked at Howard, who found his own control again at my order.

“There must be something in Chloe’s room,” he stammered. His aggressiveness had left him; he ran toward the door.

I turned to the patient, who was shaken with retching sobs.

I stayed until Chloe Barton had fallen asleep. Then I told Howard not to move her, to call her physician when she woke.

He listened, staring at me as if I were a ghost. And he is not so far from the truth.

Fuller took me home in his car. He did not talk on our way back, he only said he would see Cyril Hinds, to give him some instructions, but he made no mention of his betrayal.

As soon as I got back to my room, I rang up Schratt. My nerves were rattled. I did not want to crack under the strain. Also that infernal line “Amidst the mists and coldest frosts he thrusts his fists against the posts and still insists he sees the ghosts,” was repeating itself again, as if somebody shouted it into my ear.

When I told Schratt to discontinue feeding the brain, he disapproved.

“That’s a funny suggestion coming from you, Patrick,” he said. “Once you tried to strangle me for meddling with it, and now it’s you who are afraid of this experiment!”

“I’m not afraid!” I replied. “I will go on with it, but I need a few days’ rest. I’m human too!”

“Are you?” he asked in his slow voice, which infuriated me.

“Stop feeding that brain!” I shouted into the telephone.

After a moment’s reflection Schratt answered dryly: “No. I will not interfere with the experiment!”

I was shocked at his obstinacy, which seemed so unreasonable.

“I order you to let the brain fast for the next twenty-four hours!” I said, pronouncing each word slowly to give it weight.

“I cannot accept that order, Patrick. We must go on with it!” And when I shouted at him, he said: “Janice will be back in Los Angeles. You may need her now!”

He hung up.

I sat down, exhausted. What had got into him? How did he dare disobey my orders?

I must get to Washington Junction at once!

But I did not move. My limbs were paralyzed. I lay on my bed for hours, my thoughts spinning until they were a blur of a mass of incoherent pictures. And I fell asleep.

DECEMBER 18

The telephone rang at seven o’clock. It woke me.

I felt refreshed and in full control of myself. Schratt was right in refusing to obey me. I should not lose my nerve! Now I was grateful for his stubbornness.

Howard Donovan was on the phone. Chloe, he said refused to let her own doctor see her. She was asking for me. Would I come at once? He was afraid she would have another fit if I did not say yes.

“I have taken the liberty,” he concluded, “of sending my car to pick you up.”

I promised to come.

Pulse phoned. He too wanted to see me urgently.

I told him I would be in the hotel at lunch time.

Howard Donovan’s car arrived and took me to Encino.

Howard was waiting for me on the steps of the house. His face looked swollen, his eyes were red from lack of sleep, and he mumbled a few words I did not understand. He led me upstairs to Chloe’s bedroom, keeping his distance in front of me, as if he were afraid.

He did not enter Chloe’s room w

ith me.

The curtains were half-drawn and the sunlight fell at a sharp angle on the red silk cover of a four-poster Spanish bed. Chloe’s white face lay on a lacy yellow silk pillow. She looked at me quietly as if her emotion was exhausted.

Her breakfast had been served on a table close to the bed. Silver shone brightly, and the tray was gay with flowers, but the food was untouched.

“Hello,” she said. Her voice had a little break in it.

“Feel all right?” I asked, pulling a chair close to the bed.

Chloe looked at me with dark eyes, which made the rest of her face insignificant. Slowly she drew a thin hand from under the covers and with a shy gesture touched mine. Her fingers were cold; her pulse must have been less than sixty. She needed injections of caffeine.

“Who are you?” she asked quietly.

“Dr. Patrick Cory,” I said.

She kept on staring at me.

“Last night,” she whispered, “you frightened me. You talked like my father. You dragged your left foot. You wrote his name as he did. And you said things only he and I know!”

She smiled, concealing her uneasiness behind the gallantry only breeding produces.

“How did you know about the stamp collection? My father could not have told you that!” she said.

“I may have read about it in some magazine,” I answered, but she shook her head.

“No.”

She fell into deep thought. When she spoke again, it was to herself; she had forgotten my presence.

“I know my father has not died. I knew he would appear again, in his shape or another. I was expecting him!”

She looked at me with a sharp turn of her head, her eyes wide open. “I am sure you told the truth when you said my father had not talked to you. But now he is acting through you!”

She had an explanation of the phenomenon. She took it for granted I too would understand.

“You loved your father?” I asked.

“I hated him,” she answered. “And I did think justice had disappeared from the earth because God Himself seemed to be unjust.”

She was exalted. Her eyes with their dilated pupils were blank. The world left no image on the retina and she listened to a voice only she could hear.

“You gave Fuller the order to defend Cyril Hinds, but you don’t know why!” she said in a quiet triumph.

She suddenly laughed crazily and I expected another fit, but it did not come.

“My father wants to save Cyril Hinds from the hangman’s rope, to snatch a life from death in exchange for a life he gave to death! As you might exchange a tin of beef for another, or pay back ten dollars you had borrowed. When I was seven years old, he gave me a lesson in life, his philosophy expressed in a few words: The struggle for money in this world is the struggle for life. The rich man lives a packed life equivalent to many ordinary ones. With hired assistants, slaves, servants, secretaries, sycophants, he accomplishes things in a short time the poor man sometimes takes a year to do. A rich man’s life is a hundred times longer than that of a poor man. With money one outlives the others. Money is life itself.”

I knew now why she had asked for me so urgently. My strange action of last night convinced her I was sent by fate.

All her life she had suffered her father’s domination, waiting for the years of his decline. But he had eluded her by his sudden death. She did not want to believe he was done with living. She wanted him to return! She did not know anything about the brain’s artificial life, but she felt it must be!

I moved my right hand, bit my lips, and felt the pain. I was sitting there, not Warren Horace Donovan.

“My father’s real name was Dvorak. He came from a small town in Bohemia, in 1895. He changed his name to Donovan, lived in San Juan, and worked in a hardware store. My mother, Katherine, was the owner’s daughter, and my father’s best and only friend was Roger Hinds, the station master.”

Chloe still touched my hand, as if she needed this contact. Suddenly she glanced at me and in a clear voice said: “I’ve never talked about Roger Hinds to anybody since my mother told me about him. Not even Howard knows. I kept the secret because I loved my mother, nobody else in all my life! Only I, and Roger Hinds, loved her!”

She spoke with undeniable conviction.

I interrupted. I did not want her to lose herself in reminiscence, which had become a dangerous obsession.

“A case of jack-knives was unclaimed at the station. Your father bought it, sold the knives to the farmers, and that was the beginning of his mail-order house. I have read about it.”

She nodded. “But what the papers did not know was that he began his business with money he borrowed from Roger Hinds, the man my mother loved.”

She spoke with a sudden outburst of indignation, as if it had been her own lover and not her mother’s.

“Roger admired my father, and my father knew his power over Roger. One day, to ruin him, he asked Roger for a sum of money winch he knew Roger did not possess.”

“Eighteen hundred and thirty-three dollars and eighteen cents,” I said in a flat voice. Chloe nodded impatiently, without wondering at my freakish knowledge.

“It may have been that. Roger took it from the ticket office when my father promised to give it back to him the next day He trusted Father so implicitly that no feeling of guilt even troubled him. To ruin Roger Hinds, my father purposely held back the money!”

Her voice was as shocked as if this had occurred just yesterday, not forty years ago.

She had derived her strength to live from her resolve to avenge her mother, and since her father died she had nothing to live for. She did not want to believe in his death. She was waiting for some miracle, ready to take refuge in a world remote from our own. Suicide needs purpose and decision; drifting into the unreality of a dream world achieves the same end, easily and more pleasantly.

I had to be careful not to let her excite herself too much with the story she was telling with such conviction.

“Are you sure he did it purposely?” I asked.

“Completely!” Chloe said emphatically. There was no room for doubt in her mind.

“My father wanted to marry and he found his way blocked by Roger. This was a blow to his ego. Whatever, whoever stepped into his path had to be destroyed. He loved Roger as much as he could anyone. He was really very fond of him, but to his dismay Roger was after something he wanted himself! And Donovan felt himself betrayed.”

According to Chloe’s story, Donovan had deliberately kept the money until an auditor’s examination discovered the shortage. Hinds lost his job, and then Donovan returned the sum; he made Roger sign a receipt showing it was he, Donovan, who had saved his friend from going to prison.

When Hinds recovered from the blow, he took a shot at Donovan, whose cheek the scar marked forever. Then, despairing, Hinds hanged himself. He had not told Katherine. He was ashamed of his friend’s betrayal.

A few months later Katherine, broken down by Donovan’s constant wooing, married him. They left the town at once and settled in Los Angeles,

Sometime later she learned the truth. Donovan told her purposely when he found out she still loved Roger.

From this moment he held her by fear. He forced her to bear him children. As one of his possessions, Katherine was not permitted to leave him. He could not stand losing anything which had ever belonged to him.

The woman, her spirit broken, lived a shadowy life. Her only confidante was her daughter, whose hatred of her own father Katherine nursed.

Several of Katherine’s children, conceived in loathing and disgust, had been born dead. Only Howard, the first one, and Chloe, the last, lived. Howard was crushed under his father’s fist, never permitted to do anything he had not been ordered to do.

Donovan never gave his son pocket money, and his wife and Chloe never saw cash either. Money is freedom, it makes people independent.

Howard was never given a house key. He had to ring the doorbell like a tradesman, and the

servants kept check on his goings and comings. They did not dare cover up for the boy, for they, too, were watched by a set of household spies.

Donovan was omnipresent. He used everybody’s eyes and ears for his information. Whoever worked for Donovan gave up his own personality.

When Howard was fifteen he began collecting stamps. To get money to buy them he stole and sold small objects from his father’s house—trinkets, silver, spoons, books.

Donovan resented his son’s interest in these colored bits of paper, but he tolerated it because the boy convinced him that he was enlarging the collection by clever trading.

When Howard’s interest became too absorbing for Donovan’s jealousy, he began to compete in his son’s field and bought an expensive collection for himself.

Howard possessed a few specimens Donovan did not find in his own album and, without asking permission, he simply took them for his own collection.

At seventeen Howard had the courage to run away. To finance the adventure he stole his father’s most valuable stamps. Leaving a letter explaining his reasons, Howard fled to Europe and registered in Paris at the Sorbonne. He studied hard, took his degree in economics, then returned to the States to find a job.

There he lost one position after another. He did not realize that his father was using pressure to force Howard’s employers to dismiss him.

Donovan wanted his son back home, and, as always, he got what he wanted.

One day, broke and desperate, Howard returned to his father’s house. Instead of anger, he found Donovan waiting to receive the prodigal with open arms. The embrace was symbolic: he had his son back in his clutches!

From then on, Howard worked for his father without salary or, officially, a position. From time to time Donovan gave him money, like a dole to a poor relative. He never forgave Howard that one independent action. He did not know how to forgive.

But his son had inherited some of Donovan’s obstinacy and shrewdness. He intended to beat his father with the only weapon at his command—time! If he waited for his father to grow old, then his time would come. He did wait, silently and patiently. Every day he grew stronger, Donovan older.

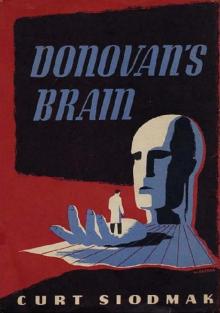

Donovan’s Brain

Donovan’s Brain