- Home

- Curt Siodmak

Donovan’s Brain Page 10

Donovan’s Brain Read online

Page 10

“Yes,” Sternli nodded. “That is what they told him. W. H. used to drink alone. Solitary drinkers are dangerous. I sometimes thought he chose to get drunk, not because he liked it, but because he wanted to blank out his thoughts. He was tired from considering so many new and powerful projects. He was hounded by his own intelligence. Often he called for me in the middle of the night and dictated for hours. I gave him a dicta phone once for his birthday, but he still kept sending for me at the most ungodly hours. Then during the last years he started to drink in secret. He did not like anybody to see and he never invited me to share a bottle with him. I think he hated alcohol, really.”

Sternli suddenly fell into contemplation, forgetting me.

So Donovan had been trying to escape himself. Did he have a conscience, then? And what was he trying to forget?

“He had coaxed the truth out of his physicians. Nobody could lie to Donovan. When he learned his days were numbered, he changed,” Sternli said.

“Became kinder, I suppose,” I prompted to help him on, but Sternli shook his head.

He polished his glasses again and smiled. His myopic eyes were wide open.

“No. Not what is generally understood by the word kindness. The first thing he did was to fire me, without a pension. He gave up his chairmanship to his son. He toned over to his family everything but the houses and apartments where he used to live. He had a score of mansions all over the country, and an apartment in every town. In each of his personal dwellings breakfast was brought in every morning whether the master was there or the bed empty. The servants had to knock, to enter, to take away the tray after a reasonable length of time. The same at luncheon. In each house each night full dinner for eight was served at the same time. Donovan loved to pay surprise visits, arrive just as the first course was served. He had found this custom described in a book about Spain in the reign of Philip II, and it appealed to his sense of seigniory. ‘I am omnipresent,’ he used to say, ‘and if I pay I expect service!’ But when they told him he was going to die, he closed all the houses. He had a plan for the limited time he had left.”

“What plan?” I asked. I felt I was close to Donovan’s secret now.

“He said he wanted to balance his books,” Sternli answered. His eyes behind the sharp glass were wondering. “I do not know what he meant by that.”

Suddenly Sternli became restless and looked at his watch.

“I must not talk any longer,” he said, as if only now he was aware he had been telling me a story he had never related to anyone before. He felt so greatly embarrassed he had to apologize.

“Forgive an old man for talking too much.”

He was in a hurry to leave, but I asked him not to go. I suddenly received the brain’s commands more strongly than ever before. As if the brain had been listening all the time and was going to take its part in the conversation now.

“Since you are unattached,” I said, prompted by the brain, “would you mind working for me? I can pay you as much as Donovan did.”

“Work for you?” Sternli’s face flushed in happy surprise. “But how could I be of service to you?”

“I want you to open an account at the Merchants Bank on Hollywood Boulevard. You will find a roll of bills in my overcoat pocket. Please deposit them,” I said.

Sternli looked myopically toward the closet, and while he was opening the door, I took the checkbook from my wallet and wrote: “To the order of Mr. Anton Sternli, $100, 000, Roger Hinds.”

Sternli returned with the money in his hands.

“How much shall I take?” he asked.

“All of it. Don’t count it. Just pay it in. And take this with you.”

I handed him the check.

The brain’s orders suddenly stopped. I felt pain creeping on me and grabbed the hypodermic which Janice had prepared for a return of the attack.

Sternli took the key and the check. He held the paper close to his eyes, stared at it open-mouthed. He had recognized Donovan’s handwriting.

DECEMBER 2

Today I got up for the first time. I shall have to wear this plaster cast for weeks to come. My back still hurts and when I move I feel like a turtle.

I can’t stay in bed any longer. Donovan is ordering me to get up, and my body aches with his commands.

Janice has to dress me; I cannot bend over. She has brought me enormously big shirts and a suit large enough for a Barnum giant, to fit over the cumbersome cast.

The brain has gained strength enormously. Its commands enter my mind as clearly as if I heard it speak, loud-voiced and determined, close to my ear.

If only I could inform it that I am out of the running. I ordered Schratt to convey that information to the brain in Morse, but I am not sure he knows Morse well enough to tap out a clear message.

I want to go back to the desert. I want to watch the brain’s development myself. But it orders me to stay here.

It has told me to get in touch with the murderer, Cyril Hinds, whose trial comes up soon.

DECEMBER 3

Sternli has opened the account in his own name and brought back a power of attorney for me. Now I can sign checks and won’t have to wait for Donovan’s signature. I asked Sternli how it feels to earn fifty dollars a week and be able to write a check for thousands.

He seemed to be shocked at my harmless joke, and stared at me aghast through his thick glasses. He stammered a few words, and I had to put him at ease again. He often watches me doubtfully since I “forged” Donovan’s handwriting so cleverly.

When Janice came in, Sternli’s blue eyes lighted up, and he forgot I was in the room. He adores her. I don’t know what Janice does to make all these men idolize her.

She is unselfish. Whatever she does, she never considers herself. That may be her simple secret.

DECEMBER 4

The brain paralyzes me at certain times. Formerly when it gave its orders I willingly followed the command. At first I was even obliged to concentrate to follow what it wanted. Otherwise my own personality interfered with the response. Now I cannot resist.

I have tried. I have fought. In vain.

Today it told me to pick up a pen and write. Janice was in the room and I did not want her to see me acting like a hypnotist’s subject.

She had just brought in my dinner and we were talking about Sternli and his strange adoration for her, which she defended smilingly, when the brain cut in. I felt my tongue tighten. I was forced to get up and go over to the writing desk. I watched my performance as detached as a stranger standing yards away from me. I wanted to stop. But I still moved mechanically.

Janice had never before witnessed a manifestation of Donovan’s will, and she was frightened. She was level-headed enough, however, not to call the floor physician.

I sat down at the desk and began to write. Janice spoke to me, astonished at first, then quickly alarmed when I did not answer.

There was nothing unusual in my attitude except the expression on my face. During this period of telepathic communication my eyes stare, my face loses all expression and looks blank as if it were made of wax.

Janice knew me well enough to be sure immediately that something like a hypnotic trance was holding me.

I wrote on the paper: “Cyril Hinds, Nat Fuller.”

Cyril Hinds was the murderer. Nat Fuller’s name appeared for the first time.

The spell ended as quickly as it had come and I gained control over my movements again.

Janice’s face was chalk. Her eyes held depthless horror.

“You were writing with your left hand,” she stammered. “The brain…”

I went back to the table and began to eat, trying to act as calmly as I could, shaken to find that for the first time I had been unable to resist the brain’s command.

“What of it?” I asked. “You know the brain is alive. It communicates with me from time to time. This step forward in my experiment will make history. Since the human brain never reaches full development during the life of the human body, I may

be able to let the brain ripen by keeping it artificially alive. This telepathic contact is only the beginning. Have you never heard that the man who experiments must be willing to take any personal risk? The world has to thank many scientists who became their own guinea pigs to achieve great discoveries.”

“But it is controlling you—not you controlling it!” She was upset.

“You are mistaken,” I answered, wanting to break off the discussion I had foreseen and dreaded. If only she had been a hired assistant, she would not have dared to challenge me. But she was my wife.

“I am submitting to the brain’s control deliberately, and I can stop any time I choose.”

Janice looked at me, pale, her big eyes dark. She read my thoughts and knew I was not telling the truth.

“Donovan is dead!” she said.

“Dead?” I said slowly. “A doctor’s definition of death is different from a layman’s. Even when a man is legally declared dead his brain may continue to send out electric waves. Sometimes a man is already dead for the physician while he is still breathing. Where does life begin and where does it end? In the eyes of the world Donovan is dead, but his brain lives on. Does that mean Donovan is still alive?”

“No,” she said, “but he lives through you. He forces you to act for him!”

“That is a contradiction,” I said. “That will not stand up under analysis.”

Janice looked at me. Her face seemed to have shrunk and it was transparent as Chinese silk. She had worried about me for years, and the conviction that I had lost myself in this experiment now broke through her self-control. I knew she wanted to avoid any serious discussion on any subject, but her concern was stronger than her resolution.

“Donovan is dead and cremated,” she said. “What you call his living brain is a scientific freak, a dangerous morbid creation you have nursed in a test tube.”

“Donovan is still alive and kicking,” I answered. “He even has written messages.”

“You derive your conviction from science,” she stated. “Mine is from faith.”

“Listen to Schratt’s disciple,” I gibed. “You are afraid! Fear threatens the integrity of the personality, but it is good for you and others to have some anxiety, some dread of consequences, some degree of self-consciousness. These restrain your dealings with others. But don’t judge my task by common codes of living. I go beyond them.”

“How far?” she asked.

“Until I understand the functioning of this brain, its will, its desires, its motives,” I said. “I am gathering facts. If I knew the relative position of all the phenomena which comprise Donovan’s brain, I could draw a parallel to our ordinary process of thinking and clear up many questions which are unanswerable now. I am penetrating more deeply into human consciousness than any man has done before.”

Janice did not reply.

I hated her at that moment. I hated her aloof, detached expression of listening to a voice I could not hear. She was guided not by her intelligence, but by her intuition. She had knowledge not gained through her senses which came from another plane that cannot be explored scientifically.

My intellectual power is based on precise reasoning. I could not deal with Janice. I was at a disadvantage.

We sat silent opposite each other.

“It has too much power over you. You cannot resist it any longer,” Janice said finally.

“Any moment I choose I can stop the experiment!”

I was defending myself and I hated her for it.

“You can’t. I just saw what is happening myself!”

I got up, walked over to the desk, and picked up the message Donovan had dictated to me.

“I wish you would leave me alone. There is no use arguing with you. I did not ask you to interfere with my work. You are disturbing me. Don’t you see?”

It was plainly put. I had to hurt her to make her leave me.

She turned without looking back and left the room.

I am well enough to live alone in a hotel where I shall not be interfered with.

The futile discussion with Janice upset me, and the tiring repetition of the lines: “Amidst the mists…” kept me awake half the night. When I got up I was shaky.

Is Donovan’s brain going insane? That monomaniacal endless returning of the same phrase indicates a decrease in intrapsychic co-ordination, an impediment of the logical combination of thoughts.

This stereotypic repetition of phonetic expressions is alarming. The sick mind imagines it hears the same monotonous sound, the same melody repeating endlessly. It considers the same situation, reproduces the same mental picture, repeats the same lines until their meaning acquires a symbolism culminating in a supernatural message, the expression of providence, which the unhealthy imagination readily accepts and interprets according to its own wish dream.

If Donovan’s brain becomes measurably insane and can still influence me against my resistance, this case will become difficult to handle. Since it already has such power over my will that sometimes I am helpless, I must think of an emergency brake to paralyze the brain at the extreme moment. I must find a solution, and soon!

DECEMBER 5

Today I went back to the Roosevelt Hotel. I feel strong enough but still must wear the plaster cast. It inconveniences me less than before.

The human body can adjust itself to most unnatural conditions.

DECEMBER 6

NATHANIEL FULLER.

The name has repeated itself in Donovan’s messages. Two Nathaniel Fullers are listed in the telephone directory. One at a gas station at Olympic Boulevard, the other a lawyer in the Subway Terminal Building, on Hill Street.

I was sure the brain means the lawyer.

I rang the office of Fuller, Hogan and Dunbar, and asked for an appointment. Fuller’s secretary inquired my business, but I could not tell her what I wanted for I did not know myself.

“Who recommended you to Mr. Fuller?” she asked.

I mentioned W. H. Donovan’s name and immediately she became very polite. A few seconds later I had Fuller on the phone.

He asked me to come in any time during the afternoon and did not ask questions. He seems a good lawyer.

It was one of the warm pleasant Indian-summer days. I took a taxi downtown. For the first time in years I felt relaxed and happy. The tension which had gripped me so long, never letting me breathe freely, driving me on and on even when I slept, had suddenly left me.

I played with the fancy of going away soon. I wanted a rest. Perhaps to New Orleans for Christmas. Perhaps take Janice with me. In strange alarm I analyzed my thoughts. I was suddenly including Janice in my future life, forgetting our misunderstandings and tensions. Was I unconsciously trying to run away from Donovan? Had I become afraid of the experiment? I must watch myself carefully and not let the subconscious interfere with my activities.

I announced my name to the girl behind Fuller’s reception desk. She picked up the phone in a hurry and a few seconds later Fuller came out. He was small and stocky, dressed by an expensive tailor, and his gray hair carefully groomed.

Packed as I was in the cast, I presented a strange appearance, but he registered no astonishment and took me straight into a room with a sign on the door: “Library. Quiet, Please.”

The silence which suddenly engulfed us was abnormal, as if the walls were specially sound-proofed. Though it was early afternoon, the Venetian blinds were drawn and neon tubes threw a diffuse light through the room and left our features shadowless. It was a good light in which Fuller could easily observe the expression in his clients’ faces.

He asked me to sit down and took a chair opposite me at the long, glass-topped conference table.

“W. H. sent you,” he said in a pleasant, unaggressive voice, and looked at me with an air of friendly lassitude.

“Yes. He mentioned your name before he died.”

“What did he tell you?” Fuller murmured.

“You have been one of his lawyers, I understand,” I said.

“And he told me I could talk to you frankly, if I ever needed legal advice.”

“You need it now?” he asked, and looked squarely at me. “What can I do for you?”

“I want you to take over the Hinds murder case,” I said.

He leaned back in his chair, which he slowly rocked on its slender legs.

“Hinds is guilty of first-degree murder and this is one of the most cruel cases I have heard during my twenty years as a criminal lawyer!” He looked down at the table and spoke slowly as if to gain time.

The soundless room may have hidden microphones. The neon lights may be there for making secret pictures.

A few dicta phones were standing about, and a voice recording machine. Perhaps every word I spoke was preserved on wax as evidence against me.

“I am prepared to pay you a bonus of fifty thousand dollars, besides your ordinary fee, if you can exonerate Hinds,” I said.

He sat silent and pondered a moment. He did not take my offer seriously and was trying to decide how he could get rid of me without offending me. The amount was preposterous, out of all proportion, even for this case.

In my cheap, ill-fitting suit, I did not give the impression of being a man who could pay a lawyer fifty thousand dollars.

I looked on the glass-covered table and our eyes met as in a mirror. It seemed a trick of his, watching people in the glass top. It annoyed me.

“Exonerate. You mean acquittal by the jury?” he asked to gain time. He was reaching for the bell.

I took a wad of money from my pocket and laid it in front of him.

He pulled back his hand from the bell.

Uneasy, he tried to get me into a discussion to find out more about me.

“Will you please tell me your motive in this, Dr. Cory?” he said.

“Just assume I am fighting capital punishment,” I answered.

He nodded. This was a basis for discussion. Many people in the world will support their convictions with good cash.

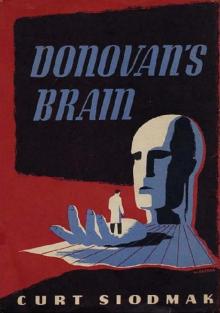

Donovan’s Brain

Donovan’s Brain