- Home

- Curt Siodmak

Donovan’s Brain Page 9

Donovan’s Brain Read online

Page 9

“Hello,” the doctor said with professional cheerfulness. “Still in pain?”

He was filling a hypodermic with morphine.

“Thanks, I don’t need it,” I said definitely.

The man looked astonished. “The pain can’t have stopped so quickly,” he said.

“I’m surprised myself,” I answered, and looked down the length of my body.

There was nothing I could feel. As if I were only a brain, I was hardly aware of arms or legs, or even my injured back.

“Would you mind testing my nerve reactions?”

He stuck me in the arm with a pin, but I experienced no pain reaction.

I felt like a patient under a spinal anaesthetic.

“Are you sure your diagnosis is right?” I questioned.

He indicated that he was.

I closed my eyes; I wanted to think out clearly what had happened to me. I heard the doctor whisper to Janice and leave.

As soon as he had gone, I asked her to get Schratt on the phone.

She hesitated and I repeated the order.

A few minutes later I was talking to Schratt.

“How are you, Patrick?” he asked, relieved to hear my voice. “Janice told me about the accident.”

Janice stood at the window with her back turned.

“I wanted to ask you,” I said slowly, prepared for the pain to return any moment, “if the brain has acted differently during the last forty-eight hours.”

He did not reply at first.

“I did not want to alarm you as long as you were ill…” he said finally, “but it seems to have a fever. I can’t make out why. The temperature rises quickly, then drops to normal when it is asleep.”

Suddenly the pains attacked me with increased fury. I thought I could not stand them. Even the bones of my skull hurt as if a fist were pushing from inside.

“Wake the brain!” I cried into the phone. “Wake it up! Knock on the glass! Frighten it! Don’t let it sleep!”

The receiver dropped out of my hands. I bit my lower lip until blood filled my mouth.

Janice grabbed the hypodermic, but the pain evaporated like steam.

I took the receiver again and heard Schratt come back to the phone.

“The brain is awake now, Patrick. The lamp is burning.” Then: “What did it do to you?”

My head sank back on the pillow. I knew what had happened and tried to tell Schratt.

“It suffers my pain when it is awake,” I said, controlled. “It suffers the pain instead of me. It seems to have penetrated my thalamus. Its cortex now receives the reflexes of my nervous system. My body’s pains are experiences in Donovan’s cerebrum. It takes possession of me more and more. Before, it controlled only my motor nerves, but now it dominates that part of my brain where pain registers.”

Schratt was breathing so loudly I could hear him.

“If this continues,” he said, “it soon will control your will.”

“What of it?” I asked, trying to speak lightly. “Some men have given more than their identity to science.”

“Yes,” he said, and suddenly hung up.

Groping, I put the receiver back on the hook.

“Now I’ll be all right,” I said to Janice. I forgot she had listened to our conversation. Schratt’s voice had been loud enough for her to hear.

Janice stared at me, her eyes wide with terror and despair. I had not known how much she knew, but now, understanding some of the consequences, she divined the abyss of destruction to which the experiment had led me.

During the last few days the pains have bothered me less, but I am still confined to my plaster prison. Even when I get up, I shall have to carry twenty pounds of cast around with me.

The brain has given me some addresses: of one Alfred Hinds, in Seattle, and of a Geraldine Hinds in Reno. It insistently repeated the names last night.

Once, impelled by telepathic command, I tried to get out of bed, but Janice, hearing my moans, gave me a shot of morphine which immediately severed communication with the brain. It was like cutting off a telephone connection. When I am drugged, the brain cannot get in touch with me. It seems at a loss to understand why I do not follow its orders.

It is not aware I have had an accident. I tried to tell Donovan about it. Lying quietly, putting myself in a trance of concentration like a yogi, I tried to transmit the message. I could not.

In my dreams and lately during the day that strange sentence returns again and again: “Amidst the mists and coldest frosts…”

Its unending repetition tortures me as much as the pain. There must be some meaning. The brain must have a purpose in repeating it.

I phoned Schratt and told him about it. He seemed amazed when I spoke the sentence to him, but he insisted he had never heard it before.

I asked Janice. Finally, after thinking it over for a day, she came to the conclusion it must be a rhyme to cure people of lisping.

That sounds likely, but why should the brain repeat such a line?

Janice and I avoid mentioning the brain. She is waiting for me to speak first, but I have not the slightest intention of bringing up the subject. She knows too much already; it disturbs me to see her ponder about it. Whatever comes into Janice’s mind is written all over her face. She would be the worst secret agent in the world.

But I am getting used again to having her around. Actually during the few hours she leaves me with another nurse in her place I feel uneasy, as if something might happen and only she could help me.

When she is not around I sometimes become sentimental about her. I recall the day when I was hitchhiking my way back from Santa Barbara to the hospital and she gave me a lift. How often she waited patiently in her car to chauffeur me around; I had to live on the twenty dollars the hospital paid its interns.

She had always been willing to give me a lift. That seems to be her function in life.

She is patient. She always was. And persistent.

She made up her mind to marry me. She did. She wanted to get me away from Washington Junction—here I am. Now she is waiting to win me back to her.

She knows when to be around and when to leave me alone. She is like a fine voltmeter, recording the slightest variations in current. How much happiness she could give to some people, instead of wasting her strength on me!

I must talk to her about that one day.

NOVEMBER 29

Anton Sternli visited me. He rang up from the reception desk first. Janice answered the phone and stepped out to meet him at the elevator.

She kept him in the corridor nearly an hour, talking to him, before she let him see me.

When we lived on the desert, Janice limited her activities to running our house. Now, taking advantage of my helplessness, she has extended her field to the people connected with me. She has always had Schratt in the palm of her hand, and Sternli has been easy.

Sternli looked more like a Swiss professor than ever when he came into the room, peering at me through heavy glasses that made his eyes look the size of hazelnuts. That suit could never have been made for him; the trousers bagged over his knees. He carried a white cane like a blind man’s.

Sternli had seen about my accident in the papers and would have come before, but he only got his glasses yesterday. He wanted to tell me how sorry he was.

He talked about insignificant things until Janice left us. She had seen in his eager face that he wanted to be alone with me.

“You startled me with that memorandum in Donovan’s handwriting,” Sternli began. “You see, before he left for Florida he gave me the key and wrote down a number. All his life he was over-cautious about everything. Even when he signed his name, he would shield his left hand with his right so no one could see what he wrote until he had finished. I am astonished he should have thought of me at the hour of his death! And why did he have my name on an envelope with money in it in his pocket? He was never generous unless there was advantage to himself: It makes me uneasy, Dr. Cory.”

/> “You judge him too harshly,” I said. I saw complications ahead.

“Oh no.”

Sternli took off his glasses and cleaned them studiously with a small piece of chamois, holding them close to his eyes from time to time.

“W. H. was my whole life. How can I hate what I was a part of? When W. H. dismissed me there was nothing left to live for. I have no family, not even a friend. To make friends one must be tolerant and interested, and with advancing age we become less and less adaptable. One has to give to keep friends, and my larder is empty. There are two species of man, the creative and the imitative. I am the latter. And those people are very barren if no inspiration comes from outside.”

He spoke quietly. This was his philosophy; he expressed it without bitterness.

“I have been approached by a publishing house to write a book about W. H. They offer me a great sum of money and I need it for the future; my salary was too small for me to save.”

Sternli was eager to talk. He sensed that my relation to Donovan was closer than just that of the one disastrous meeting. He could not define the bond between me and his former master, but he felt impelled to talk with me to free many unspoken words.

He never had spoken to Donovan as he did to me. His natural shyness and fear of his master had prevented it. Still, for years Sternli had hoped in his heart that some day he would find the courage to talk to him as one man to another. Sternli never did.

Now with Donovan’s death that hope had died, but speaking to me was like confessing crimes of which, though only as his master’s tool, Sternli was somehow the villain.

He told me his life story, typical of a retired, studious fellow like him, secluded from the world.

Sternli had worshipped Donovan to a degree which destroyed his own personality. Donovan had accepted this devotion and, without any qualms, had taken every possible advantage of the man who would not or could not live a life of his own.

In Zürich, where he was studying languages, Sternli met Donovan. When he saw the millionaire for the first time, in the most expensive hotel, of course, the scholar was immediately fascinated by his powerful personality.

That afternoon Sternli had bought himself a cup of coffee at the Baur-au-Lac Hotel, just to see for once how the rich of the world lived. While he was drinking his coffee slowly, Sternli heard Donovan’s booming voice calling for a man to translate some wires into Portuguese. He could hear the frightened desk clerk’s apologetic reply.

In a rare fit of courage, which marked the turning point of his life, Sternli offered his services.

Donovan kept him around while he stayed in Zürich, and when he left he asked Sternli to accompany him as his secretary. The young man jumped at this opportunity to see the world.

Sternli became Donovan’s shadow, intimate to him as a pair of spectacles. He slept next door to Donovan, followed him from conference to conference, from town to town, from country to country, from continent to continent.

Donovan’s secretary, letter-writer, interpreter, but never his friend, Sternli grew into his job, became the walking, living memory of the intricate machine which was Donovan’s brain.

He never took a holiday; he would not have known what to do with himself. Only once, when his mother was dangerously ill, he asked for a short leave of absence to visit her.

Reluctantly Donovan agreed, and when Sternli asked him for money for the trip to Europe, Donovan made him sign a personal note for the five hundred dollars.

In telling this story Sternli skipped over a part of his life. I could only guess at what he wanted to conceal.

He had been in love once. As fate ironically decided, it was with Donovan’s wife, Katherine. She must have been a beautiful woman, aloof and unhappy. She did not encourage the shy young man; I assume she never even knew his secret adoration.

One day honest Sternli could not stand the conflict that raged in his conscience. He felt he was not working honestly, and also it seemed disloyal to him to be in love with his employer’s wife.

So one day he asked Donovan to release him from his duties.

Donovan immediately offered Sternli a raise. Discontent could always be cured with money. But Sternli wanted to confess.

“You are in love with Katherine!” Donovan said calmly. “What does she say to that?”

Sternli, of course, had never talked to Mrs. Donovan about it. For him to fall in love with a married woman was a plain violation of one of God’s commandments.

“If you haven’t told her, there is no reason to quit,” Donovan said sanely, and added: “There is no reason to raise your salary either.”

With this decision Donovan settled the incident to his own satisfaction. Sternli stayed on. His mind had been made up for him, even in this most intimate and important concern of his life, his love. This made Sternli more dependent than ever.

A few months later Katherine Donovan died.

All the time Sternli was telling me this, he did not give the impression of being a naturally talkative man. He was just relating facts, without so much as a quiver in his voice. Only sometimes, to punctuate a grave revelation, he smiled, took off his glasses, and wiped them carefully.

He talked on, calmly, unpretentiously. He wanted to get closer to me, and with this story he succeeded in doing so.

I am certain he did not know why he opened his heart to unreel his life story to a stranger, but slowly his and Donovan’s characters gained shape and color. I learned more about Donovan from listening to Sternli’s life story than about Sternli himself.

It interested me very much. I had overlooked this obvious approach. Donovan’s story as told in the magazines was exaggerated, falsified, yellow-journalized. Here his real self unfolded.

I began to understand the brain’s workings. If I could search Donovan’s character thoroughly, exploring every emotion of his heart, every reaction of his consciousness, I would understand many of the brain’s paradoxes.

I urged Sternli to continue. Like a good psychoanalyst, I tried to read the involvements hidden beneath his words. The parts he unconsciously concealed—because to him they seemed of no importance—I fit together to fill in the gigantic jigsaw puzzle of a powerful man who resolved every pang of conscience and every fit of weakness into a smashing assault on his adversary, as a boxer attacks savagely when he finds himself in a corner.

Sternli’s was an idealized picture of Donovan. He was blind to his master’s faults. He did not even divine how this man had distorted the pattern of his existence, cunningly, patiently, and thoroughly.

It became clear to me that from the moment Sternli confessed a love for Katherine, Donovan had plotted his destruction. Not that Donovan was jealous. He was too big to permit himself that weakness, but somebody had trespassed on his property. Even though the crime was committed only in thought, Donovan felt cheated and robbed.

Sternli told me about Donovan’s habit of having people spied on by detectives. Everyone close to him was under secret supervision. Number one of his suspects was Katherine. I was sure Donovan had known every step she took, was informed how she spent every minute of her time. He had checked up on Sternli, too, as a matter of routine. His watchdogs had trailed this little man.

Sternli’s eyes got bad. He slowly lost his sight and became unfit to take Donovan’s rapid dictation. Another secretary had to be engaged.

Sternli was of no other use than as a living filing system, an infallible record of things past. Since his usefulness was now cut by half, Donovan logically cut Sternli’s salary in half too. And one day he began to collect the five hundred dollars he had advanced years before—in five-and ten-dollar installments out of Sternli’s curtailed salary.

When Sternli found himself hard-pressed, Donovan acted surprised.

“Don’t tell me you have no money! You must be rich!” he said. “You must have made enough on the side.”

Sternli, deeply hurt, defended himself.

“I am not insinuating you filched coins from

my pocket,” Donovan said. “But surely you threw in a few hundred dollars too, when I bought stocks, didn’t you?”

Sternli had not even thought of such a thing, and according to his strict code it would have been dishonest.

Only once had Sternli seen Donovan weak and uncontrolled. The day Katherine died. She escaped Donovan’s domination by quietly slipping out of his hands. By dying she had deprived him of the final victory of subduing her. To hold her he had forced her to give birth to one child after another. Only the first and the last had lived, Howard and Chloe.

When Katherine died, Donovan made Sternli stay in the room with him constantly. Sternli watched the big man walking up and down for nights, mumbling to himself.

To have seen Donovan in an hour of weakness was a sentence of destruction, as if a slave had known where a king’s treasure was hidden. Opposite me sat a man of fifty who looked seventy, half blind, helpless, penniless.

“I don’t know why Mr. Donovan sent me the five hundred dollars, Dr. Cory. Exactly the sum he loaned me and then collected again! Five hundred dollars. Did he choose just that sum with some purpose? Did he want me to believe he regretted many things he had unconsciously done to hurt me? I am sure he always meant to be kind. He did not die without remembering me! It is not the money, it is the thought that makes me happy.”

“He did not know he was going to die,” I said.

“Oh yes,” Sternli replied quietly. “He had known for more than a year that his days were numbered.”

The revelation shocked me. It suddenly put Donovan in another light. It gave me a perspective on his character I had not had before.

“How could he have known about the accident in advance?” I asked, surprised.

“Oh, he did not,” Sternli answered with a wan smile, “but he knew he was ill. There was no hope. The doctors gave him only one more year.”

“Nephritic,” I diagnosed, remembering the color of Donovan’s face, whitish, with a yellow tinge. He had suffered from nephritic degeneration of the kidneys, which is usually associated with a similar process in the liver.

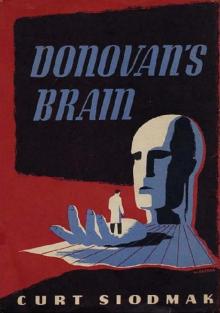

Donovan’s Brain

Donovan’s Brain